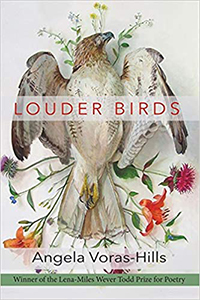

Louder Birds

by Angela Voras-Hills

(LSU Press, 2020)

Reviewed by Katherine Hollander

The best in the collection—wonders that include “Never Eat a Polar Bear’s Liver,” “Krakow,” “Chateaubriand,” “When We Were Prey to Nothing,” and “In the Beginning”—posit a strange and tender relationship between a sometimes-befuddled subject and her sometimes-broken environment. The speaker is affectionate towards, and alienated from, both the natural and the human (although these poems rightly look askance at that artificial divide). They both confess and celebrate: “we brought guns to the firehouse bake sale,” the speaker in “Bake Sales” tells us, “we caught the carpet-mouse, left him / asleep in a box with crayoned windows.” In this poem, as in a number of others, childhood is charged with relish and menace. In winter, “We raced to the front porch to lick / the icicle hanging from gutter to ground,” and in summer, children are given “five dollars for a Dixie cup full” of lemonade by men who, perhaps friendly, perhaps sinister, then “[drive] away waving, their lips wet.”

In “On Earth as It Is in Heaven,” a jubilant mother rides her motorcycle to Las Vegas and drinks “cocktails in the sun” just days after cancer treatment, but this triumph is placed next to a childhood memory of a grandfather whose “friend learned he had brain cancer and shot himself.” His widow is unconsoled by floral arrangements, prayer, or “ham and potato casserole” in a church basement, but still, and in the face of all this, the family stocks its freezer with abundant fish from the same lake “my grandpa landed his plane on.” In the wonderful “Maps of Places Drawn to Scale,” “a van flips on an exit ramp” and provides the occasion for a meditation on how birth, death, and community are different in small towns and large cities:

[ … ] At a Chinese buffet,

Death is stuffing her cheeks

with crab rangoons, while a family

stands behind her with empty plates. Nobody stuck

to the vinyl booth finds ‘You will suffer’

inside their cookie, but it’s implied

These poems—funny, sad, unflinching—are typical of the collection in the way they productively commingle ordinary but authentic pleasure, flawed human connection, and the threats of death and harm.

This threat of harm runs through the collection like barbed wire through a field. When it works, it is part of the rigor that infuses the book, giving it a powerful shrewdness and frugality—though the images of violence, particularly that visited upon animals, can sometimes feel grotesque. We encounter a drain full of dead eels fed upon by flies, a dying worm consumed by millipedes, a field of crow parts crunching underfoot, two separate bleeding rabbits, and a doe that “flipped / over our hood and dragged her back legs / across the highway into the woods.” This violence is often effective. For example, the car-struck doe appears in the beautiful “Controlled Burn,” along with a dead but still-speaking vole and a “chorus” of living frogs, who advocate on opposite sides of a debate about heaven. In this poem, the question of violence and death is a real question, complex and nuanced, and the contradictory answers are inflected with humility and forbearance.

Similarly, “Preserving” (one of my favorite poems in the book) moves from luscious plenty and human care to bleak humor or worry and back again several times, tracing the preservation of a summer’s worth of lemons to a tumble on winter ice:

[ … ] When I fall,

I catch myself with my face.

When I fall, I go

to the hospital, to make sure

the baby is still alive.

There are so many small things

to worry about in a large way.

Here, injury and the very real threat of personal loss are tempered by an understanding of the haplessness of human destruction—of the environment and climate, of animals, and of other humans, including a botched death row execution. Toads thrown into a pond by children in the mistaken belief that they are frogs will still drown, regardless of the children’s good intentions, but nevertheless “we can’t blame them for not knowing / what swims, what sinks, what floats.”

At other times the proliferation of physical harm approaches gratuitousness, what it represents or portends unclear. Instances of mundane or believable injury (the pregnant woman’s fall or the doe struck by the car) are joined by more fantastical ones (a speaker who paints the mouths of strangers shut with glue, or one who spontaneously “slit[s] the skin” of ermines “to warm my neck”). These two sorts of violence—fantastical and mundane—are both adroitly conjured, but they sometimes seem to undermine one another, making it harder to take either variety with the seriousness it demands. Instructions toward an ethics of violence—how should we understand this? Should we stop it? Can we, and how?—are not forthcoming. This perhaps weakens the collection, but it is also part of its spell. It feels of a piece with the half-imaginary midwestern world Voras-Hills conjures so well; like the real Midwest, it feels plain, clear, and very, very confusing, intolerant of obfuscation and mysticism but also profoundly obscure, profoundly mysterious in its total refusal to offer explanations—if you belonged, the poems both demonstrate and lament, fondly concede and stubbornly protest, you’d already know. This is itself an incantation (assisted by the poems’ consistently oracular titles, like “Wait in the Bathtub and It Will Carry You”), and the spell works. But there are moments, too, when we might wish for a little more mercy, a little more clarity.

Yet it is clear that Voras-Hills is a poet of seriousness and talent, one whose vision is attentive, unsparing, and, in the end, compassionate. In the very first poem in the book, she presents us with a girl “holding a plywood sign that reads: / zucchini / and God / in red paint,” tells us that “her hair snarls in the wind / and rain, but she doesn’t notice. Like any sign,” Voras-Hills reminds us, “it’s difficult to know how seriously to take it.” This difficulty, this question of seriousness, these signs—these are the worthy subjects of her poetic scrutiny. And there are no easy answers. But the poet’s precision, the beauty of her language, and her comfort with the obscure and the unknowable offer, if not a rescue, a reprieve. “For now, the puddle remains / unnamed,” she tells us, “so it is not yet a disaster.”

No comments:

Post a Comment