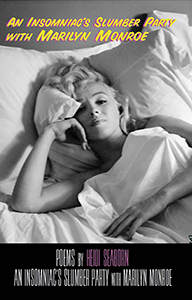

An Insomniac's Slumber Party with Marilyn Monroe

by Heidi Seaborn

(PANK Books, 2021)

Reviewed by Mary Ellen Talley

From the initial pages of An Insomniac’s Slumber Party with Marilyn Monroe, Heidi Seaborn illuminates the life of a public diva from Hollywood’s Golden Age who was trapped in a sex kitten culture. Seaborn brings Monroe to life in lyrical poems that demonstrate knowledge of and sensitive care for her subject. The poem “Marilyn” begins:

She arrives: a gardenia in a cellophane box,

petals of honeyed hair radiating.

Each blade of light travels the bud

of her dimpled chin. How like a child,

holding a buttercup to know the future.

It’s all there, in the corsage of her lips.

Lest we forget how this gentle giant of an actress forged her popularity, Seaborn suggests it in “All I Ever Wanted,” a zig-zagged, abecedarian, persona poem, “God gave me a childhood from / hell & no father. But Heaven help me— / I have real talent & work I so love! I will never give it up.”

The adage goes that the best poetry shows, rather than tells. Poems in this collection brilliantly show how a woman worked within a patriarchal system to gain advantage but ultimately was unable to break free from all its constraints.

In 1951, a pinup girl named Norma Jeane signed with Twentieth Century Fox studios and became the starlet Marilyn Monroe, a breathy-voiced comedic actress the public came to adore as they followed her career and celebrity marriages.

She remains a movie icon some sixty years after her untimely drug overdose death in 1962 at the age of thirty-six. At a book launch, Seaborn said her goal was to explore celebrity culture and create persona poems with pieces that enter into “conversation” between poet and subject. Seaborn demonstrates how deep engagement with a subject’s life can resonate with a writer’s own experience. For example, Seaborn discovered both she and Monroe suffered from insomnia.

Rather than breaking the book into sections, Seaborn disperses early morning insomnia entries throughout as if someone is being tormented by a luminescent clock face. “Insomnia Diary” begins eleven short poems randomly placed to suggest the speaker’s disjointed anxiety and wakefulness. The entry “1:26am” begins:

I’m patrolling tonight’s borders

for a scrap of sleep to roll and smoke.

I crave Ambien and a limey vodka tonic.

It’s the middle of the night and Marilyn’s here

without a lick of makeup in my kitchen,

wrapped in a creamy silk robe. Like mine.

The anachronism of a modern era sleeping medication reveals how this poet interweaves subject and speaker in her poems. In a reading through Skylight Books, Seaborn juxtaposed Monroe’s anxiety, insomnia, and addiction to barbiturates with the speaker’s challenges with insomnia. Regarding this interweaving, Seaborn shared that “the speaker also discovers she’s addicted to Ambien.” (https://www.crowdcast.io/e/skylit-seaborn)

for a scrap of sleep to roll and smoke.

I crave Ambien and a limey vodka tonic.

It’s the middle of the night and Marilyn’s here

without a lick of makeup in my kitchen,

wrapped in a creamy silk robe. Like mine.

In another series of six clock time gems, “Hello, it’s Me, Marilyn,” we read persona poems of Monroe making phone calls on the night of her death: to her physician, to the actor Peter Lawford, to her makeup artist, to her miscarried child, and to her mother. The words are heartbreaking to read as they seem to inhabit Monroe’s pain.

Three selfie poems give Monroe entry into a modern cultural phenomenon she might’ve embraced had she lived. Seaborn excels at persona poems in voices that shift and merge. She also offers acrostic, abecedarian, prose, mirrored pairs, and list poems.

Three selfie poems give Monroe entry into a modern cultural phenomenon she might’ve embraced had she lived. Seaborn excels at persona poems in voices that shift and merge. She also offers acrostic, abecedarian, prose, mirrored pairs, and list poems.

“Divine Marilyn in Paris” is a set of twelve ekphrastic persona poems relating to a 2019 exhibition of Marilyn Monroe photographs and artifacts. Persona poems fit right in with Monroe who created her own public image and provided fantasy for her fans.

Monroe emerged from poverty. One of the twelve persona poems, “[June 19, 1942–Portrait of Norma Jeane on her Wedding Day to Jim Dougherty]” suggests why she married at age sixteen. Aunt Grace admonishes “at the end of my high school sophomore year: / ‘Marriage or the orphanage, your choice / Norma Jeane.’”

Neither her youth nor her stardom provided Monroe with an idyllic life. A poem with easy flowing couplets, “Sometimes I Just Want to Be Norma Jeane,” begins “I slice myself in half like a lemon, / leave Marilyn in the vestibule.”

The title poem “Insomniacs’ Slumber Party” uses lines from a 1967 interview with Judy Garland about Marilyn Monroe. In the poem, actual insomniac characters— Judy, Poet, and Marilyn—chit chat about taking too many sleeping pills, “Judy: so you take a couple more / Marilyn: sleeping pills to sleep. / Poet: That’s what they’re for—to sleep.” Readers can recognize an all-too-familiar and contemporary dependency on prescription drugs that continues to plague our society.

If imitation is the highest form of flattery, Seaborn delivers several poems that take inspiration or spin off from the work of several modern poets she admires. For example, in “Selfie with Marilyn Monroe,” Seaborn plays with the list form of a Diane Seuss poem, “Self Portrait with Emily Dickinson.”

Many fans came to realize that Monroe wasn’t a “dumb blonde” even though she played the part well in many sexy comedic films. Once she was photographed with her copy of James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” The prose poem “Reading Ulysses” includes:

that’s what I was reading when everyone

assumed I was reading only the dirty

parts so that’s what they wrote in the

paper about me reading my first edition

that I bought at the Strand and carried

everywhere so while the photographer

was fiddling with the film I pulled it

out to read.

In keeping with the title and thread of insomnia, how perfect to end the book with “Then I Slept,” a quiet poem inspired by Ada Limón’s “The Last Thing.” The initial poem of the book, “1:28 am,” begins on a downbeat, “I’ve taken Ambien every day this week” with the presence of a sleeping lover “flaming a fire.” By contrast, in “Then I Slept” the speaker notes the indentation of “still warm, my love’s body” after having “slept without Ambien’s dark / fist pressing my pillow.”

assumed I was reading only the dirty

parts so that’s what they wrote in the

paper about me reading my first edition

that I bought at the Strand and carried

everywhere so while the photographer

was fiddling with the film I pulled it

out to read.

In keeping with the title and thread of insomnia, how perfect to end the book with “Then I Slept,” a quiet poem inspired by Ada Limón’s “The Last Thing.” The initial poem of the book, “1:28 am,” begins on a downbeat, “I’ve taken Ambien every day this week” with the presence of a sleeping lover “flaming a fire.” By contrast, in “Then I Slept” the speaker notes the indentation of “still warm, my love’s body” after having “slept without Ambien’s dark / fist pressing my pillow.”

Seaborn begins this last poem of her collection with the exquisite sour-sweet line, “First there was the lemon peel / of morning,” only to end the poem and the book:

the heavy perfume

of daphne drifts through an open window

and a hummingbird whirs over the forsythia.

In the stacked white boxes

up the hill, the honeybees doze.

Mary Ellen Talley’s Book reviews have been published in Compulsive Reader, Crab Creek Review, Asheville Poetry Review, Empty Mirror, Sugar House Review and The Poetry Cafe. Her poems can be found in many journals and anthologies. A chapbook, Postcards from the Lilac City was published by Finishing Line Press in 2020.

of daphne drifts through an open window

and a hummingbird whirs over the forsythia.

In the stacked white boxes

up the hill, the honeybees doze.

Mary Ellen Talley’s Book reviews have been published in Compulsive Reader, Crab Creek Review, Asheville Poetry Review, Empty Mirror, Sugar House Review and The Poetry Cafe. Her poems can be found in many journals and anthologies. A chapbook, Postcards from the Lilac City was published by Finishing Line Press in 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment