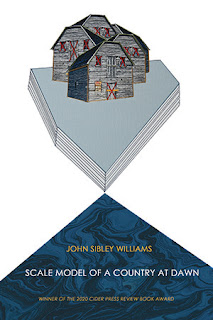

Scale Model of a Country at Dawn

by John Sibley Williams

(Cider Press Review, 2022)

The landscape of loss is a personal topography we traverse when those who are dear to us die. In his new book of poetry, Scale Model of a Country at Dawn, John Sibley Williams contemplates loss and its aftermath in poems that depict life’s evanescence and beauty with clarity and grace. Winner of the 2020 Cider Press Review Book Award, this collection offers nuanced perspectives on mortality that suggested to me a glass paperweight containing a microcosm. The reader encounters the crumbling houses of childhood, dark forests, a cliff, burning barns, the “multi-colored living field,” islands. These archetypal landmarks effectively connect the speaker’s experiences with memories and emotions from the reader’s own life.

Scale Model of a Country at Dawn opens with “The Gift,” a prologue in which the speaker pledges to make and give “something the light must struggle to enter.” Throughout the book there are allusions to profound losses in a muted elegiac tone. Williams’ studied restraint creates enigmas of loss so that reading the poems is akin to unearthing the bones that once comprised a body’s architecture, or smelling the smoke that lingers after fire. Carefully placed hints snagged my attention, and I felt compelled to read and then reread the entire book to better understand these losses and their ramifications.

The book’s eponymous poem begins with an epigraph defining a Hobson’s choice, the decision to accept or refuse the one thing offered. Time offers the quintessential Hobson’s choice: move forward or not at all. The only possible way to return to the past is through memory, a model of dubious verisimilitude by virtue of limited perspective and emotional refraction. It is important to note the time chosen for regarding this model of the past, since dawn implies the rebirth of hope, perhaps even joy, as the world of light, color, and clarity returns following a period of darkness.

The title poem consists of unrhymed couplets, the form Williams uses in the book’s first and last poem and in almost one-third of the collection. Enjambment spills images over lines and across the spaces between stanzas in a cleaving that severs, then connects thought:

Either side of a saw, either a beheaded mountain

or not enough coal to last the winter; a startled

horse beats itself against an open barn door,

imitating flight, while the hay catches fire, &

emptied of organs, painted to look less still,

my mother has never looked more herself.

After a parent, caregiver, or another person integral to one’s life dies, memories and unanswered questions are likely to become focal points in which the relationship’s dynamics as well as the survivor’s self-regard are scrutinized. Scale Model of a Country at Dawn conveys these struggles and complicated emotions with admirable honesty. These beginning lines from “Controlled Burn” convey dread and doubt with ominous imagery and terse analogies:

Acre after acre left unburnt.

Full families of wolves gone

unshot. & the chickens we keep

to teach our children where meat

comes from are getting nervous.

The wire-thin pen cannot stop

the world from entering. Like how

quitting cigarettes only delays

a mother’s cancer. Like all those

desperate prayers that refuse

to restrain night.

Williams employs an ampersand in place of the word “and” even at the beginning of an utterance that culminates in a full stop, as seen in the excerpt above. The use of a symbol to represent this conjunction echoes the poet’s skill at weaving symbolic meaning into myriad images of animals, objects, and geographic features. There is, however, one poem about two-thirds of the way through the book that didn’t have ampersands nor the double slashes that appear in some other poems. The switch to formality gave me pause. I was curious to know the reason behind this choice, and the change caused me to slow down and read more carefully. “Fever” begins:

When you hold your child’s body like this,

cold as unexcavated earth, wet with want,

making oaths to anything that will listen, please

and god and the usual silences, so much useless

splendor cradled fetally between raw open hands.

When the field just keeps going without you.

The poem is stunning in its heartbreaking vulnerability. Of all the memories considered in this collection, the formality in this particular poem bespeaks exceptional anguish. As Emily Dickinson wrote, “After great pain, a formal feeling comes—” The frame of reference in “Fever” may well be, in Dickinson’s words, “the Hour of Lead— / Remembered, if outlived.”

The terror and shame in “Fever” are associated with “dark steepled night” and “gut-shot worship.” Left with “the usual silences” after a terrible event or devastating loss, even the most stalwart believers might well question their convictions. Certainly I did with the death of my grandmother, and then decades later when I lost my father and youngest brother. The poems in Scale Model of a Country at Dawn alluding to death and doubt resonated. Williams conveys the anguish of loss and the memory of trauma with extraordinary sensitivity. As I read these poems, I felt an empathic kinship with the speaker whose experiences of loss and doubt were superimposed on my own.

The contemplation of one’s own mortality is given vivid evocation in “Synonyms for Paradise,” a poem near the beginning of the book. Williams writes:

It hurts me to do it, but let’s let the synonyms

for joy & for grief bleed together, like salt

& fresh water, like poles of a magnet.

That we all die before we’re finished

is no excuse to abandon this worn-out

car by the side of some nameless road,

flipped over, only partially on fire.

That we should know when we see it

is not the same thing as a promise.

The stark truth “we all die before we’re finished” is followed by a whimsical metaphor comparing life to an old car “flipped over, only partially on fire.” The dry humor conjured by that description never fails to make me smile, yet the next statement is a profound challenge. Within the poem and throughout the book, juxtaposed opposites like “joy” and “grief,” “salt,” and “fresh water” perfectly balance one another.

As in all the poems in this book, musical intonation carries the reader through “Parallax,” a gorgeous poem that combines the profound and the ordinary in shifting perspectives and indentation:

One could almost say

illusion, that all this seeing

is a trick the light plays to keep us

rooted in place. In this case,

driver, subject. If things worked out

differently, we’d be out there wandering the object-heavy night

dreaming that our raised thumb meant

you can trust me & unarmed, then drinking

the moon from crushed cans rusting by the road.

The last section of the book, “Object Permanence,” is notable for poems that seek resolution and find endurance in a considered acceptance. Tentative joy emerges from the ashes and regrets, and gradually the sharp outlines of loss begin to blur. The speaker regards his own children with wonder akin to breath caught in surprise and released in awe. In one of the book’s last poems, “Restoration,” we read:

In the absence of repair, I’ll make due

with telling my children this failing house

& the country we planted it in & the world

that refuses to stop blooming around us

& the stars can be shelter enough.

During our lifetime, each of us travels through our own little country with its own particular landscape. Yes, there is loss, but there is also love, beauty, and hope. As the poem “Larynx” proclaims, “the world is worth singing into.” In Scale Model of a Country at Dawn, John Sibley Williams urges us to savor the journey and cherish those with whom we travel.

No comments:

Post a Comment