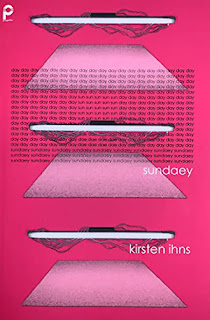

sundaey

by Kirsten Ihns

(Propeller Books, 2020)

“There’s something to be said about not saying anything.”

—Janet Jackson

“I know / I don’t know / that’s what I do know”

—also Janet Jackson

Sans serif on the hard pink shell of the cover greets the reader of Kirsten Ihns’ debut poetry collection sundaey. The flamingo-milk-stained edges of the book are ostentatious and cube the rectangulation of the outer presentation; this dimensionality further brings it to life. I know, I know, a book, its cover… judging! But the performance of the color captivates like a robin’s egg.

Note: I know Ihns and attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop with her. For the purposes of transparency and ethical behavior, that must be known. I consider this to be a re-view versus a review, and I consider that distinction to not only allow but to explain my compulsion to write.

Perched in the “day,” a block text in limbo between the table of contents and numbered pages, “sun” then “daey” are presented. More of these block-text poems will emerge throughout the pages, almost migratory in their return back to meaning and with something small flitting in to disturb them.

The introductory poem is “yes, hello.” It is a strange beginning. It is rattling to begin with a confirmed response. In my own rereadings, I gloss the first couplet then read “I was taken out to dance and click.” Here and throughout the book, Ihns boggles with her specificity. I want to laugh at it as a line. It feels like all it can be doing is humorous. The last two words stretch the sincerity of the entire line. This is later followed by “mostly, I like things I can find.” This seems to be a crucial creation method for Ihns, her ability to listen and find, yet before the line can even end it plunges back into “by means of batherwater / behavior.” With the turn, she is no longer nest-collecting an identity but bobbing in bathwater to find. What bird is this?

The “i have left The Amazing Hair Day, for you” first line of the second poem, “the world of flying motor objects,” is instantly humanoid and shifts with the following lines into a demand. It is lyric, it is appealing, and it is “v” self-aware. However, it is not self-identifying. Much of the collection is self-aware and even alights momentarily near self-conscious. In “of the five senses, desire is the sixth,” the creature-speaker acknowledges creatureness but admits “sometimes it’s hard to know one is.” Yes.

Sometimes the poems preen and carefully tumble line by line, but mostly they dart around as if trapped in/on the cage/page. Line uniformity seems to scare the speaker; it is avoided. In its place, sound is prioritized. Sometimes words seem to only exist because of their sound. Each a careful tweet (and often tweetable) moment that builds into song. Then “lol wat.”

The warble of the longer forms, while grounding the sometimes-flighty collection, blends seamlessly into the smaller chirping one-page poems that are sonically strongest. These poems are “the kind of pleasure you can gnaw and not diminish,” and it is often difficult to differentiate between their playful sensuality and their playfulness. Each so wholly convinces the reader to get caught up in the rapture of their sound.

Speaking of “rapture,” after a book-length deluge of good and great poetry, this poem is something beyond. It is a spectacular poem that I still find surprising three years after its publication (originally online in BOAAT). A person could spend years with this poem. I did. I will continue to. Each time I teach it, students are marveled by its seeming simplicity and eventual density. And the last three lines! After experiencing “rapture,” one can return to the page before page one and see in block text of “day” a door of “sun” and “dae.” This is what the book is, “a new door” leading to “the same building / as the others.” It’s a bird’s-eye-view of the door and it is also an invitation inside.

There are moments to openly chortle: I don’t know how to read the title “quat swan” and not laugh. That is the grammar of Ihns’ debut. And by “quat swan” it is all beginning to be a language of its own, understandable when one follows the flight. Then the Greek mythological figure Leda appears in the poem, or actually, the speaker commands the reader not to be “reading that in.” The repetitive negative command is a trick to the human mind and a confirmation that one should “reference to leda in the swan” regardless of what the speaker says. Again specificity turns the entire myth on its head with the replacement of “and” with “in.” As if Yeats’ sonnet needed further complications, Ihns steps in and complicates. This poem begins by engaging in hilarity and sacrificing then resurrecting the swan “on the lawn / like geese.”

This is the part where the ruse of the lyric-rouged lines begins to truly glimmer through. The speaker seems most “honest” as a bird, as a creature, as anything that is not human. Even inanimate objects have believable sentience in her lines.

The eye feathers of I-statements are a wonderful vehicle to guide the reader along a carefully curated flight path. Any other thing with eyes knows how to follow. When lines like “i refuge like my body is adornment” come it is both definitely contrived and certainly sincere. Then there are lines that are a way for the reader to “fix it how you like it,” although this writer cedes no control.

A desperate bird will lure predators away from a nest with hopping and singing—any successful distraction. In this debut, Ihns is birdlike, though her distraction-song is not desperate, but consciously useful. By the end, a reader may be encouraged to lean away from trusting her “I.” The lyric continues to appear on the page but it is mostly pecked to near-death, cannibalized to serve the sound of each line. Trusting the musicality of the Ihns' lines is far more successful.

Out of the pink shell of sundaey hatches a knowledgeable bird: capable of human imitation like a crow, yet tropically showy. Even when contemporary means a time and not the now we know it, Ihns will never be accused of writing contemporary poetry. Instead she offers sundaey, “a new door,” a novel method for meaning makers to experience the strange.

What does it all mean? Sometimes it’s warning. Sometimes mourning. Sometimes it’s a playful morning tune. Most of the time it flutters between f**king and I-don’t-f**king-get-it. In that fluttering, the music of the verse remains undeniable. This is a strong first collection and an important debut.

No comments:

Post a Comment