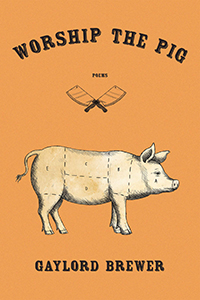

Worship the Pig

by Gaylord Brewer

(Red Hen Press, 2020)

Reviewed by Star Coulbrooke

This could be called a book of odes, of praise songs, of quests punctuated with wry asides. Of poems saying not what the poet starts out to say, but what the poems say instead. Take the introductory poem, “When It’s Done Right,” the play on Mary Oliver’s dictum that “happiness, // when it’s done right, / is a kind of holiness.” This poet of worship has “enraged / with joy” the “flies and chiggers” that leave “welts on ankles.” He tames the “lunging dragon” of snowmelt on the mountain to “a kitten in a necktie.” He compares the “cough of a tractor engine” to the “plaintive caw of raven,” and proclaims the “dull day ahead / free of usefulness,” all to get at something important, something portentous. Which, when he gets down to it, has been “happily forgotten.” Instead, the poem has already said what it needed to say. This kind of happiness, the giving-up of poetry to its own holiness (salted with a little blasphemy) is what keeps us reading.

“Worship the Pig,” as title poem, lends itself succulently to praise, singing of the “Holy loin, blessed shoulder,” “Sacrament / of rib, ham, jowl, and hock,” the “sweet white fat, well salted.” Even the slaughter and burning succumb to such human longing that the process from pasture to table becomes a state of grace. At the end of it all, “we” (granted, not everyone, but those who’ve read on, appreciating the wit and wonder of the words even if they don’t eat pork), “eat in thanks, pig hallelujah.”

The praiseworthy pig appears in one other poem, “Solution to a Morning of Little Possibility: Frying Bacon.” As an ode, it begins by setting a scene, moves into a sort of prayer, imagines/imparts value on the object of desire, and ends with a sense of one’s life having been altered.

The scene begins with the object of desire being prepared by characters akin to altar boys:

Get the big skillet from its hook,

peel off one unguent strip at a time,

butchered and cured

down the road by some old boys

who worship the pig,

and load that thing up

over medium-high heat.

Moving into the prayer, hands and mouths forming the supplication:

Get your hands greasy, deep

in the pores, stand over it

working the rhythms until

your glasses steam,

your tongue’s wagging in a wet mouth.

Now the desired object, adored, deified:

Bacon takes care of bacon,

the unctuous agency of pork,

the holy salt-flesh and sweet-fat

better than Jesus

and Elvis rolled together.

Finally, an alteration, a transformation, an urgency that decries the normal state of being, that transcends the ordinary:

Get the whole house smelling good,

the dog on high alert.

Damn it, son. This may be

the best day of your wasted life.

Need we say, in the spirit of James Wright “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota,” that the poet has drawn from the best of his forebears to craft this ode for all of us who love a good meal? It doesn’t matter that our tastes are worlds apart; whatever we prepare with our own hands and partake of with relish and gratefulness is worthy of such an ode.

Robert Hass, in his 446-page A Little Book on Form: An Exploration into the Formal Imagination of Poetry, devotes nearly a hundred of those pages to the ode. “The word in ancient Greek,” says Hass, “meant ‘song.’” The form evolved from “longish” lyric poems with complex emotional thoughts to less formal free-verse poems and praise poems, pausing for the romantic odes of Wordsworth and Coleridge. Hass quotes M.H. Abrams describing the ode as “an inward journey,” which involves the eventual transformation or alteration referred to in the bacon poem above.

Here is a praise song not about food or pork (though it does mention breakfast at one point), but about parents, and the poet’s take on their aging process. The poem starts with a scene, which is nearly fully described in the title, “On a Clear, Hot morning in Brazil, Balcony Overlooking Mountain and Sea, I Think of My Parents in Kentucky.”

The title scene continues with the parents waking in their home after not enough sleep, going to the bathroom, making coffee and “their first adjustments to the day’s pain,” as they talk about “their youngest son’s unending restlessness.” The description continues with his father’s “twisted wrists,” “deafness,” and “shuffling frailty,” and his mother’s “swollen ankles” and “cold that won’t leave.” The poem has now turned to the inward journey of the poet’s song, in which he questions his intentions and transfers the anger-stage of his own grief to the reader at the same time:

Why am I telling you all of this, these intimacies

that break my heart and have broken theirs,

this sadness shading every gesture, that turns

paradise into a senseless rebuke? Listen, this poem

is none of your goddamn business. Nor the paltry

options of the day ahead. Forget joy. How about

any distraction to kill an hour, to hold back the walls?

Hass writes that the praise poem comes out of “litany and prayer” (the litany of parental ills and broken hearts), with the beginning “initiated by desire or dissent” (the poet’s desire to share his parent’s intimacies with readers while dismissing them at the same time). The middle section can be variable, according to Hass, but might name the object of desire, imagination, or value. In this case, is it the parents? Or the poem? Or perhaps the audience the poet pretends to dismiss?

The final section points toward asking a favor from the object or power the poem has elaborated on. This poem seems to do the opposite, as readers are told, “I don’t want you knowing any of it, or your opinion.” He doesn’t want “your sympathy” for this “unbearable cocktail of helplessness.” After all, he asks, isn’t this “the oldest story in the world, and the most banal?”

Sure. Until it’s yours, these two you love dearly,

sixty-five years together with hardly a night apart,

whom you miss already as they leave you step by step.

We’ll see how tough you are, when the time comes.

In the end, as the poet is transformed, so too are his readers. He’s speaking to them through his experience, but he is also speaking to himself through them. The ode has shaped itself into what it needs to say and be through the craft of a canny poet.

The poet’s craft extends throughout the book, in every poem, from the confessions of a self-remonstrating animal lover to the comedic delight of life in a foreign country, to the sweet and sorrowful admonishments of humanity as it revels in the sheer joy of paradox “in this big-ass world,” “full of romp and circumstance.” This book of odes, “Done Right,” spans continents and topics in its journey to a holy kind of happiness, though certain readers may at times be advised to apply a grain of salt. For anyone invested in the succulent nature of poetry, this is praiseworthy work.

No comments:

Post a Comment